Dean James D. Anderson's Promise Fulfilled

by Tom Hanlon / Jun 28, 2021

James D. Anderson came from humble but strong roots. His nearly five decades of academic excellence and leadership has fulfilled what he calls “a moral obligation to succeed” and honors the sacrifices of his mother and grandmother.

When James D. Anderson, dean of the College of Education, received word that he had been elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences this spring, he was surprised.

“You don’t see it coming,” says Anderson, whose 47-year career at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign has been filled with awards, honors, and prestige. “When I see my other Illinois colleagues who were elected, whose work I respect so much, and when I see the other people around the nation who were elected, it’s a tremendous honor, one that ranks at the top of the list.”

If Anderson had trouble seeing the honor coming this year, think what the 8- or 10- or 12-year-old Anderson would have said, had somebody told him then where would be today.

“There’s no way in my wildest dreams back then I could imagine doing the things I’m doing now,” he laughs. “I was just trying to get through the moment at the time.”

Anderson’s ideas about the future when he was growing up in Eutaw, Alabama, were shaped by his knowledge of where—and who—he came from.

Overcoming Oppression and Obstacles

Eutaw was the site of racial terrorism in the years following the Civil War, culminating in the 1870 Eutaw riot, when Ku Klux Klansmen lynched or fatally shot about a dozen Black men and wounded scores more, to suppress Black Republican voting. Most Black Republicans either stayed away from the polls or voted Democratic in that year’s gubernatorial election. (The Democratic candidate ended up winning by 43 votes; in the 1868 presidential election, Republican Ulysses S. Grant won the county by 2,000 votes.) In 1868, the county courthouse in Eutaw was burned to destroy the records of about 1,800 freedmen against planters who were about to be prosecuted. Lynching increased in the late 19th century and early 20th century across Alabama.

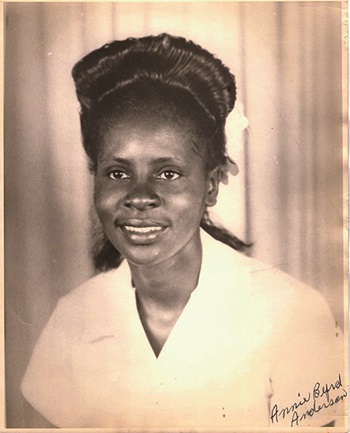

Against that violent and oppressive backdrop, Anderson’s grandmother, born in Alabama to slaves, was intimidated from going to school, and never went. His mother, Annie Byrd, was forced to stop her education after ninth grade. That was, at the time, the farthest the county allowed Black students to go.

Against that violent and oppressive backdrop, Anderson’s grandmother, born in Alabama to slaves, was intimidated from going to school, and never went. His mother, Annie Byrd, was forced to stop her education after ninth grade. That was, at the time, the farthest the county allowed Black students to go.

“That gives you a sense of the place my grandmother and mother were born in,” Anderson says. “You just wonder what their lives might have been like if they’d been able to get a good education and advance themselves.”

Anderson’s grandmother determined that her daughter would go as far in school as she could. Annie Byrd did that. Annie, a single mother, was bent on her four boys going farther than she did. They all did that.

“My mother’s initial expectation was that we all would finish high school,” he says. “She told us we couldn’t miss a single day of school, and she wanted us to have complete attendance certificates and complete respect for the teachers, no disciplinary problems. Not one of us had a single disciplinary problem.”

Knowing his grandmother’s and his mother’s experiences, Anderson says, resulted in him feeling a moral obligation to succeed, to go farther than they did, to overcome the obstacles thrown in his pathway.

“We grew up knowing people would try in so many ways to keep us from getting a good education, from advancing,” he says. “I felt like I was in the fight for the long run.”

Exceeding Expectations

Annie Byrd passed away in 1994. By then, she had watched with pride and joy as her son Jim not only graduated from high school, but from college as well. He then attained an M.Ed. and a Ph.D. from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He became an assistant professor, and then an associate professor, and finally a professor in both Education Policy Studies and in History. And earned a Distinguished Scholar Award from the College of Education.

She got to witness all this. To see how far he had come, how far he had exceeded her own educational accomplishments and any expectations of him. It is every mother’s hope that her children go beyond what they themselves experienced and achieved.

She got to witness all this. To see how far he had come, how far he had exceeded her own educational accomplishments and any expectations of him. It is every mother’s hope that her children go beyond what they themselves experienced and achieved.

Anderson gave his mother that gift many times over.

“I had a grandmother who didn’t have a chance to go to school at all, a mother who was cut short, then I got all the way to where I am,” he says. “It hits you with what can happen in one generation if you close the opportunity gap. If you give kids an opportunity, that can take them way beyond the generations that went before them. It’s not that I was smarter than my grandmother or mother. It’s just that I got the opportunities that they never got.”

Making the Most of His Opportunities

James D. Anderson has made the most of his opportunities. He has spent nearly five decades in leadership positions in education. He has taught and mentored and tutored countless numbers of students who have gone on to their own sterling achievements. Among his numerous publications is a book, The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935, that won the American Educational Research Association (AERA) Outstanding Book Award. In 2020 he received the AERA’s highest honor, a Presidential Citation.

“The continuous influence and impact of that book was monumental in shifting histories of education focusing on the experiences of African Americans and racial minorities, as written by scholars of color,” says Professor Yoon Pak, head of Education Policy, Organization and Leadership (EPOL). “It has enabled international audiences to gain a deeper understanding of how race in the US and access to education, or lack thereof, parallels similar struggles globally.

“More importantly, his research and achievements have opened the disciplines of history and sociology as well as the field of education research to a new generation of scholars who have produced award-winning scholarship themselves. He has mentored countless numbers of budding and senior scholars throughout the decades.”

Anderson was elected to the National Academy of Education, considered the highest honor in the field of educational scholarship. He has served as an expert witness in a series of federal desegregation and affirmative action cases, and as an advisor for and participant in several PBS documentaries. He has garnered numerous honors at the University of Illinois, among them his selection as a Presidential Fellow. He became dean of the College of Education in 2017 after serving for nearly a quarter century as department head for EPOL.

“Dr. James Anderson is the College because of all that he represents through his decades of research, teaching, and service,” Pak says. “I marvel at how he has continued to do so with great humility, grace, and generosity.”