Alumnus Makes Surgical Training Model a Reality in Africa

by Tom Hanlon / Sep 14, 2022

The AmoSmile team in Rwanda; alumnus Anthony Dwyer pictured second from right.

Anthony Dwyer, Ph.D. '22 EPOL, is part of a team that has created training modules to virtually train surgeons in carrying out reconstructive surgery on patients in limited-resource environments. Dwyer’s work has been directly influenced by what he learned through the College of Education’s Learning Design and Leadership program.

Sub-Saharan Africa is the world’s hotbed for reconstructive surgeries. People in this region annually require more than 16 million reconstructive surgeries to treat wounds and defects caused by burns, trauma, cancer, and congenital conditions. These conditions lead to disability, joblessness, pain, stigma, social isolation, mental health issues, and educational barriers.

Yet, Rwanda, for example—a sub-Saharan African country of 13.6 million people—has two plastic surgeons.

AmoSmile—an Operation Smile and AmoDisc collaboration—is doing something about that.

Anthony Dwyer, vice president of medical technology and innovation for Operation Smile, is part of the AmoSmile team, which has representatives from 10 countries across the globe. Dwyer earned his PhD in Learning Design and Leadership from the College of Education in May 2022, and his experience in the program has helped AmoSmile become one of four finalists for a $1M grant offered through the Global Surgical Training Challenge. Initially, 75 teams entered the Challenge, funded by the Intuitive Foundation.

Helping Surgeons—and Patients—in Resource-limited Countries

“Hospitals are overwhelmed,” Dwyer says. “So, the question is how do you train the next group of clinicians in the area with limited funding? Here at the University of Illinois, it’s wonderful, because I have a 64,000-square-foot simulation center [the Jump Simulation Center], 3D printers, and computer-aided design software. They don’t have that in Rwanda.”

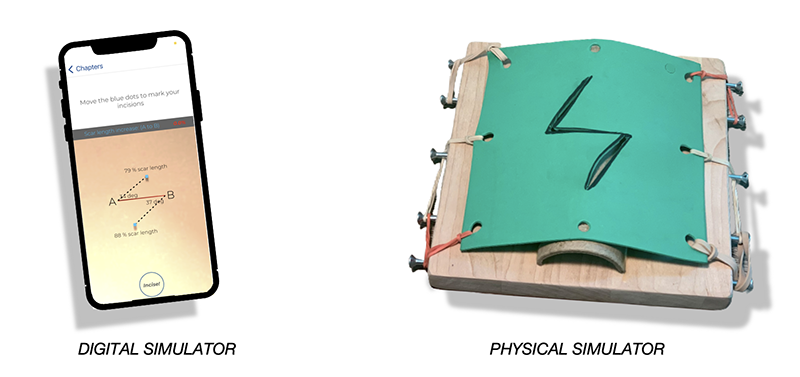

The answer: design a low-cost simulator, build a curriculum, and create a training application that can be accessed through cellphones to provide clinicians the knowledge and experience they need.

In doing just that, AmoSmile has created a surgical training model that incorporates virtual learning modules and simulations to teach surgeons how to restore form, function, and feeling through local flap surgery called Z-plasty. The procedure calls on the surgeon to cut a Z-shaped flap where the burnt skin has fused together, to open up scar tissue and provide greater range of motion and mobility.

“We had to design a locally-sourced, low-cost simulator using everyday items available to people in Rwanda,” Dwyer says. “They have wood, they have nails, they have string or twine, they have tissue-like substance. We take a toilet paper roll and bend it to give it a little curvature and we can spindle it up to get the surface tension to be just like skin. And we can do all that for less than $5."

That’s the physical side of the simulator, a tool to learn with.

The tool to learn from comes from the training app.

A Training App for Reconstructive Surgeries

The app provides step-by-step modules designed to facilitate self-directed learning and training for local flap surgery. “It provides the clinical knowledge, the foundational knowledge of pharmacology, anatomy, and physiology, to be able to safely care for a patient,” Dwyer says. When trainees have proven their mastery of the information through a test bank, they use the app to show that they know how to conduct the procedure. “We can walk through an entire surgical case or clinical procedure without touching a patient,” Dwyer says. “Attending surgeons give them feedback on their hand control, tissue control, suture length or spacing, the amount of depth they took with their scalpel, and a million other things.”

Besides equipping doctors with the knowledge and expertise to perform Z-plasties, the training modules and app greatly cut down on attending surgeons’ time. Many times, an attending surgeon will spend 10 days in a foreign country, with eight of them focused on providing the foundational knowledge and technical skills, Dwyer says. “Now, we can jump almost right to the end. Now, it’s show me that you can do these things, and I’ll give you real-time feedback.”

The final outcome is trainees learn critical elements of the Z-plasty procedure, including understanding which flap to select for different reconstructive requirements, best practices for designing these flaps, and the step-by-step approach to performing these procedures. And they learn the optimal way of performing closure, so they can achieve the best reconstructive results for their patients.

The Learning Design and Leadership Program Influence

Professors William Cope and Mary Kalantzis of the College of Education first met Dwyer at the University of Illinois College of Medicine Peoria, where Dwyer served as director of simulation education and scholarship.

“Anthony took us on a tour of the simulation center, and what we saw there was amazing,” Cope says. “He was considering enrolling in our online doctoral program [Learning Design and Leadership]. We were immediately struck by the broad educational implications of Anthony’s work.”

The Learning Design and Leadership (LDL) program attracts people from across many fields of endeavor, Cope says. “In the health area, for instance, we have a physiotherapist evaluator from Singapore, a medical informatics researcher at Washington University in St. Louis, an administrator in the Medical School at Stanford University, and a leader in the national nursing accreditation agency,” he says. “These people bring such a wealth of knowledge and a thirst to apply educational principles to the work they do. These are people who are having an enormous impact on the world.”

The program has grown solidly in recent years. “We now have over 200 master’s and doctoral students,” Cope says. “In fact, we’ve had to reject a huge number of extremely well-qualified applicants. With new LDL hires, however, we hope to be able to accept more.”

The program “peeled back the onion” for Dwyer in how to teach adult learners. “How do you measure the level of competency for someone walking into the operating room?” he asks. “For hundreds of years, it’s been ‘See the procedure being done, then perform it yourself, then teach your fellow resident or colleague.’ That’s not safe or efficient. How do we produce results, how do we standardize results? That’s what I was looking for. Doctors Cope and Kalantzis opened my eyes to ubiquitous learning.”

Ubiquitous learning involves the use of digital content, mobile devices, and wireless communication to deliver teaching and learning experiences to users anytime and anywhere.

“They also really opened up those doors for me, showing me that yes, it’s okay to change [in terms of adult learning approaches],” Dwyer adds. “Now that we have this technology, we can lean on it a little bit more.”

The LDL program stresses that learning is bidirectional. “You should be getting something from your learners, whether it’s kindergarten all the way up through professional levels. You should be learning how to educate well and better every day,” Dwyer says.

“What LDL taught me is to put together a curriculum using instructional design methodologies,” Dwyer continues. “I like to use the ADDIE model: Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement, and Evaluate."

Helping the Most Vulnerable People on the Planet

By the end of the year, Dwyer will know if his AmoSmile team was awarded the $1M prize.

“If we win, we will get to partner with MIT Solve and the Intuitive Foundation to solve other problems of training in medicine education,” he says. (MIT Solve is an initiative of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with a mission to drive innovation to solve world challenges.)

“If we don’t win, we’ll go on regardless. We’ll still go out and treat kids around the world. Operation Smile is in 38 countries, and we do this work every single day. We have 2,600 surgical activities in 16 different specialties planned for our academic year.”

The simulator that the AmoSmile team has been working on has tremendous potential, Dwyer notes. “I hope it allows us to diminish the patient backlog,” he says. “Through simulation-based medical education, we can train up surgeons and provide them the skills they need to help the most vulnerable patients we have on the planet.”

Dwyer is effusive in his praise of Cope, Kalantzis, and the LDL program.

“Projects such as this wouldn’t be possible without their insights,” he says. “Doctors Cope and Kalantzis set me up for success. Without them I wouldn’t be where I’m at. Who would have thought that from my little home office in Trivoli, Illinois, I’d be creating simulation-based medical education for people around the globe, training people in Rwanda or Guatemala or Nicaragua or in 38 countries around the world?

“They’ve been a real blessing. I needed them to help me help others all around the world."

Learn more about our Learning Design and Leadership program.