Populating higher education with diverse leaders

by the College of Education at Illinois / Oct 12, 2016

When Jim Anderson was working on his M.Ed. and Ph.D. at the University of Illinois, he was the only African-American graduate student in the Department of History and Philosophy of Education, which later became the Department of Educational Policy Studies (EPS).

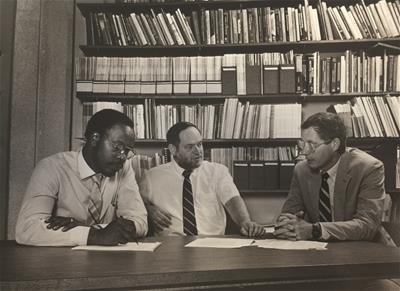

When he returned to Illinois and the College of Education in 1974, after a three-year stint at Indiana University, Anderson was the only scholar of color in EPS, which is now the Department of Education Policy, Organization & Leadership—and he remained so until 1983, when Bill Trent was hired.

If that makes the College sound like a setting where diverse ideas go to die, nothing could be further from the truth. Anderson returned to Illinois precisely because of the openness within the College to expanding diversity.

“I knew the support I received as a graduate student. I knew how open they were to different ideas,” he said.

Ahead of the diversity curve

Anderson saw what the College was trying to accomplish and how ahead of the curve it was on the issue of diversity. And he observed a white leadership that championed diversity long before others did. He decided to join in.

Even so, it was an uphill battle for many years, one that changed incrementally through the recruitment of black and Latino students.

“Right about the time Bill came, around 1983, Paul Violas, my adviser when I was a graduate student, had the bright idea to go to many of the historically black colleges and bring bus tours of the students to this campus,” said Anderson, interim dean of the College of Education and an Edward William and Jane Marr Gutsgell Professor of Education. “We had at least 100 or so students who came up, and we didn’t get a single application!”

But the College slowly gained traction in this area through contacts and began to attract more African-American students, many of whom have gone on to become highly renowned professors, including Stafford Hood, who is the Sheila M. Miller Professor in Curriculum & Instruction and director of the Center for Culturally Responsive Evaluation and Assessment.

But the College slowly gained traction in this area through contacts and began to attract more African-American students, many of whom have gone on to become highly renowned professors, including Stafford Hood, who is the Sheila M. Miller Professor in Curriculum & Instruction and director of the Center for Culturally Responsive Evaluation and Assessment.

“We started with a group of students who went on to very successful careers,” Anderson said. “And they started to recruit at national conferences. Another thing that helped was three years later when campus initiated SROP—the Summer Research Opportunity Program—which brought in hundreds of talented, high-achieving undergraduates who were interested in graduate school. The key thing was for our faculty to be their mentors over the summer.”

Anderson and Trent, who also is a professor in EPOL, mentored numerous students involved with SROP. Students who came were primarily from historically black colleges and from the West Coast, and SROP helped them prepare to apply to graduate school.

“We also went to the University of Puerto Rico, where we tapped into a literal gold mine of students who became successful in STEM,” Trent said. “So we began to get a strong Latino population from Puerto Rico.”

Thus, the pipeline of black and Latino students began. Trent said the College also has a legacy of students from Korea and other Asian countries.

“That connection began after the end of the Korean conflict,” he said. “Some members of our department, Harry Brody in particular, went to Korea to help the new government plan its new educational system. So students from South Korea started to come here for graduate school, and that built over time. There was a point in the mid-‘80s when about a third of our graduate students were from South Korea.”

Seeds planted by early college leaders

While on the surface little diversity could be seen when Anderson began as a professor at Illinois, he saw the seed that was planted, and by the mid-‘80s it was beginning to sprout. The seed was established by a number of leaders in EPOL, Anderson said, scholars such as Joe Burnett, who later became dean; Clarence Karier; Paul Violas; and others.

While on the surface little diversity could be seen when Anderson began as a professor at Illinois, he saw the seed that was planted, and by the mid-‘80s it was beginning to sprout. The seed was established by a number of leaders in EPOL, Anderson said, scholars such as Joe Burnett, who later became dean; Clarence Karier; Paul Violas; and others.

“Sometimes people attribute the push for, and increase in, diversity to me, and sometimes to both Bill and me, but the support they gave us, the leadership they gave us, was the critical ingredient,” Anderson said. “They brought me back here specifically for this effort. Not to take it on by myself, but to be one of the pieces of the puzzle. You need broad-based support from all faculty. I knew in coming here I wouldn’t have to start from scratch and sell them on the importance of having a diverse faculty. They already had and promoted those ideas. So I came into a context where we were ready to go to battle. And we did, and we won.”

Anderson noted that early proponents of diversity, such as Violas and Karier, faced discrimination surrounding their Greek lineage and German-farming heritage, respectively. They were therefore well aware of the issues they would face in order to create an environment where students are welcomed and feel included and supported.

“We may not have had exactly the same experiences, but we had experiences that were similar enough that we could talk to each other and we could understand across boundaries,” Anderson said. “That was the context that made it possible for a lot of things to happen in this department.”

And a lot has happened in the department—so much so that Anderson said they no longer keep track of the number of scholars of color within. He guessed that at least half of EPOL faculty is of color. The department also has gone from one woman in the department when Anderson arrived to about half of the faculty being women.

“We’ve been extremely successful in attracting a high number of scholars from diverse backgrounds, partly because our students have been very successful,” Anderson said. “They’ve gone on to become deans and provosts and endowed chairs. We have graduated people who go forth and carry our values and their ideas across the country. It’s what our students have done since they’ve left here that has had the greatest impact.”

An enriched intellectual environment

The idea of diversity boils down to listening to and considering different viewpoints and voices. Living out that idea has become the hallmark of EPOL, as typified by Trent’s classes.

The idea of diversity boils down to listening to and considering different viewpoints and voices. Living out that idea has become the hallmark of EPOL, as typified by Trent’s classes.

“I went to an undergraduate school that was all white,” Trent said. “I had an opportunity to learn how to listen to voices that are different. Most students today still don’t get to experience that. So I make sure my classrooms are safe places where students can begin to have the experience of learning to listen across boundaries. A part of that has to be intentional. So here we have an opportunity to create research teams that are gender-mixed, race- and ethnicity-mixed, age-mixed even. So on top of the normal academic rigor, you also have this subtle type of learning that’s going on where they can call on each other.”

A benefit of diversity, Anderson said, is the dynamic development of an enriched intellectual environment.

“Students learn that whatever sacred beliefs you come in with, they’re likely to be disrupted by someone who has had a very different experience and very different beliefs,” he said. “And that disruption compels everybody to think more complexly about matters. It shakes them out from any comfortable beliefs that they have.”

Recruiting and graduating scholars from underrepresented backgrounds—a moral imperative and way of life

The University of Illinois does not have an ocean or mountains. It does not have the bright lights and glamor of New York City or Los Angeles. Still, Anderson believes it’s a place where students can creatively “imagine” and “experience.”

“When you come and see what it’s like to be here, you see we have something that other places don’t have. When people visit, we have no problem closing the deal. They know this is a special place. They know it through our current faculty and even more so through our graduates. So we remain one of the most attractive places in the country.

“What’s going on at Illinois has been building for decades,” he continued. “This was not done overnight. We knew it couldn’t be done overnight. But it developed, and it took off. Now students know our legacy. They know that black students and other students of color have come here and been successful, and they want to follow in their footsteps.”

In a 2016 piece published in The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, Christopher M. Span, associate dean for academic programs and an associate professor in EPOL, noted the diverse talent that annually comes from the College of Education at Illinois.

This spring, 12 African-American women—known as the “Talented 12”—earned doctorates in EPOL; one African-American woman earned a doctorate in Curriculum & Instruction; one African-American woman earned a doctorate in Special Education; and six African-American men and 11 Latina/o students earned doctorate degrees in the College this year.