Navajo Scholar’s Indigenous Leadership Research Aids Educators of Native Students

by Tom Hanlon / Feb 7, 2024

Oliver Tapaha’s research pushes the boundaries of Indigenous-centered, culturally-responsive education and leadership. Through it, he gives Navajo and other Indigenous peoples a voice and a way to reconnect with their roots.

Academic researchers are much like archaeologists: They go on a dig, hoping to discover something important. Through persistence, they often are successful.

At times, they discover something they weren’t looking for—something as valuable, perhaps even more so, than the original treasure they sought.

Such is the case with Oliver Tapaha.

Tapaha, an Illinois Distinguished Postdoctoral Scholar in the Education Policy, Organization & Leadership (EPOL) Department in the College of Education, is a citizen of the Diné (Navajo) tribe from northeastern Arizona. (“Citizen” means he is more than one-quarter Navajo.) He came to the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign in the fall of 2023 as a DRIVE (Diversity Realized by Visioning Excellence) postdoc scholar. For one of his projects last fall, he wrote a chapter on the history of Navajo education from the Navajo Long Walk in 1868 to 2000 for an edited book.

And that research led him to an important discovery.

“When I was looking into the history of Navajo education, I learned that Black educators came to the Navajo Nation to teach,” he says. “They were recruited to teach on the Navajo reservation after the 1954 Brown versus the Board of Education decision.” In that decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that laws establishing racial segregation in public schools were unconstitutional.

Tapaha is working with two colleagues on this new project. “It’s an important work because it’s really unknown,” he says. “It will be new information for everybody. This year marks the seventieth anniversary of Brown versus the Board of Education, so it’s a timely piece of history that nobody knows about. It’s important to unwrap it and share it with the public.”

Embracing Indigenous Education and Leadership

Tapaha’s heritage and culture are of great importance to him. His maternal clan is Naakai Diné’e (the Mexican People Clan) and his paternal clan is Hónágháahnii (The-One-Who-Walks Around Clan). His family bond, including both sets of grandparents, is extremely strong. He grew up speaking the Diné language and hearing the stories of his elders, of the ancient ways of life. His parents taught him to never forget his roots and encouraged him to get a good education so that he could walk in two worlds at once.

He is doing just that.

“We need more Indigenous scholars,” Tapaha says. “Navajo education and Indigenous education are under-researched. And the people who do the research are outsiders who come in and get their information and then write about it.”

Instead, Tapaha says, what’s needed is scholars who come from Indigenous communities and who go back to their own communities to shed light on what’s taking place in the schools and how to address education issues.

“That’s my mission; that’s what I’m passionate about: sharing my own experiences and others’ experiences, some of the struggles that we have had and how we’ve overcome those struggles,” he says. “I want to help people to rethink and recenter their work on how to embrace what Indigenous education and teaching and learning and leadership is and looks like. That’s what drives my work.”

Two Areas of Research

Tapaha focuses his research in two main areas: Indigenous leadership in K-12 and higher education, and tribal educational sovereignty.

“I am an ethnographer and I value biographical and autobiographical research,” he says. “I research the lived experiences and stories of people, particularly of Indigenous leaders in K-12 and higher education.”

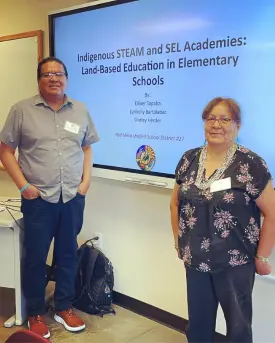

To that end, Tapaha is also working on a reflective narrative this semester on the organizational and leadership strategies that he used to implement two types of Indigenous programs into elementary schools on the Navajo reservation (he has 12 years of K-12 teaching experience in a locally-controlled tribal school and two public school districts on the Navajo reservation).

“I did several talks around campus last fall, talking about this project that I implemented in two schools, and it really resonated with people because I was tapping into the local community’s knowledge and bringing that into the schools to create the programs,” he says.

Tribal Sovereignty and Native American History

Tribal sovereignty, Tapaha says, is about “taking back what belongs to us, about exercising self-determination. It’s building upon the culture, the language, and the history that exists or that has been disrupted and reclaiming that back.”

Tribal sovereignty isn’t just an educational issue; it’s a tribal issue as well. For example, he says, it involves “our tribe being able to monitor research activity on tribal lands so that no additional harm is done to the people and to the land and to the resources that exist on the Navajo reservations.”

Tapaha is also part of a multidisciplinary effort to improve the resources and support services that K-12 teachers in Illinois need to effectively teach Native American history. That effort is being led by faculty in the American Indian Studies Department and History Department.

“My colleague and I, who is a postdoc here as well, have had a few conversations with Yoon Pak (head of EPOL) about how we can contribute to that project,” Tapaha says.

“Dr. Tapaha is on the cutting edge of developing ways to apply indigenous leadership and methodologies to advance culturally responsive and sustaining leadership,” Pak says. “He has the direct experience as a school leader and the research knowledge to contribute to the field of educational administration and leadership. His contributions have direct relevance for any and all school leaders for truly inclusive practices.”

Culturally-responsive Leadership

Indigenous-centered, culturally-responsive school leadership and education has always been at the core of Tapaha’s work.

“I’m really pushing to ensure that this research reaches educators in Navajo schools and in tribal schools like the Bureau of Indian Education schools and public schools on reservations and schools with a predominantly high population of Native Americans,” he says. “It’s important to hear the voices of students, the voices of educators and scholars like me who are doing this work, and learning from our experiences and then transferring that knowledge into practice.”

His reflective narrative project will showcase the organizational skills and leadership skills that he used in schools on the Navajo reservation.

“I want to provide readers a framework of the skills that are needed to carry out some of these practices in the school setting,” Tapaha says. “A lot of it is me diving deep into my own culture and language and how I was raised. Also, looking at how my parents and grandparents carried out their leadership practices.”

Respecting His Roots

It’s safe to say that Oliver Tapaha’s lived experience and the lessons he learned from his parents and grandparents is quite different from most of the readers of this story. Tapaha was raised in a one-bedroom house with no running water, plumbing, or electricity. He slept on a mattress on the floor. The nearest highway was eight miles away; the closest supermarket was a one-hour drive. He did his homework by the light of a lantern.

But he was raised in love and to respect his culture and roots. He developed an appreciation for where he came from and who his people are. He lives out his respect and appreciation through his work—passing down to succeeding generations of Diné and other Indigenous tribes so they can gain that same respect and appreciation for their culture and roots.

“I want students to understand who they are, where they come from, and how they can contribute back to their community based on the knowledge that they’re gaining in the education system,” Tapaha says. “And the knowledge they’re gaining from the environment and the community because those are equally important.”