Thinking Hands: How Gesturing Can Help Us Understand Difficult Concepts

by Tom Hanlon / Oct 30, 2024

Quick Take

- Researchers are exploring how video learning environments that prompt gestures can potentially enhance learning.

- The project is evaluating an approach to designing video learning environments for teaching statistics concepts, using gestures during instruction and cueing learners to perform gestures.

- The design principles emerging from the project could support learning challenging ideas in multiple disciplines.

Can I get away without using my seatbelt? Is it time for me to ask for a raise at work? How safe is it to skydive?

Whether you know it or not, you use statistical reasoning every day to make decisions. You consider the consequences of not using your seatbelt, of asking for a raise, of taking risks.

But studies show that many people have serious misconceptions about probability and statistics. Those misconceptions can lead to poor decisions or missed opportunities.

A team of researchers from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and Purdue University has just embarked on a three-year study to evaluate the impact on learning statistics in a video-learning environment that encourages students to produce hand gestures.

“Hand gestures” might sounds like a formality, such as the signals made by traffic cops or a “thumbs up” to indicate agreement. However, hand gestures are an extremely common and natural part of human communication. And if you’ve ever observed someone gesturing when on a cell phone or when trying to solve a geometry problem, then you know that gestures do more than communicate; they also help us think.

But can asking students to make gestures make a difference in the learning and understanding of statistics in online and remote learning environments?

Michelle Perry thinks so.

Communicating With Our Hands

“In normal face-to-face interaction, we use our hands to communicate,” says Perry, a professor of Educational Psychology in the College of Education at Illinois. “The hands carry a lot of information in terms of additional details or modifications of the verbal message. They provide the observer with crucial information. A teacher can glean what a student is understanding if they’re paying attention to what’s coming out of the hands, because it can provide different information from what is conveyed in speech.”

Robb Lindgren, a professor of Educational Psychology and Curriculum & Instruction agrees.

“The hands have a particularly special role with the type of learning that we’re aiming to generate in this project, which is developing the ability to explain complex ideas in statistics,” he says. “Key ideas like variance and central tendency have a spatial component (e.g., distribution, distance, etc.) and so gesture can play a special role in explaining—and understanding—these concepts. A student can use their hands to show a distance or show a distribution. We believe that prompting students to use their hands in this way can help them develop more robust and resilient statistical knowledge.”

Collaborative Effort, College Ties

Perry and Lindgren are core members of the team that is headed by College of Education alumnus Jason Morphew, principal investigator for the project and an assistant professor of Engineering Education at Purdue, who earned his Ph.D. in Educational Psychology at the University of Illinois. Other core members include Karle Flanagan, a teaching associate professor in Illinois’ Department of Statistics, and Shereen Beilstein, a research specialist for the Illinois Workforce and Education Research Collaborative, which is housed at the University of Illinois’ Discovery Partners Institute. Flanagan received her Ph.D. in Curriculum & Instruction at the College of Education; Beilstein earned her Ph.D. in Educational Psychology, where she studied under Perry.

“We’ve got three alumni—Jason, Karle, and Shereen—really taking a lead role in this project,” Lindgren says. “It’s heartwarming to see them ascend to these positions, to see them develop as researchers, and, in the case of Karle, seeing an excellent instructor in statistics take what she learned from our College and apply it to her practice. Despite this being a distributed and diverse team, it is pretty incredible that we all have our origins in the College of Education.”

Designing Video Learning Environments

The project will evaluate an approach to designing video learning environments for teaching statistics concepts. Those environments will use gestures during instruction and cue learners to perform gestures. The work will unfold in three phases.

“We’re starting off with interviews with both experts and novices, reasoning about statistical concepts, not with any particular learning goals in mind but trying to get them to just talk about these ideas and to use their hands when explaining them,” Lindgren says. “That work will inform the next phase, which is having the students view videos with different ways of engaging the viewer with gestures, depending on their assigned study condition. The last phase will look at a smaller number of students to try and understand the effects of gesture cueing on their in-video learning and on subsequent explanations that students give.”

The concepts being used in the study are central tendency (including mean, median, and mode), variance, and linear regression. “In one of the conditions,” Perry explains, “students will be asked to produce gestures that align with the statistics concept being described in the video. We’ll test whether or not we see differences in students’ developing understanding of these concepts when they are cued to gesture.”

Students in the study will include both undergraduates and high school students from Illinois and Indiana. Some of the undergraduates will be STEM-focused; others will not. “We’ll look at the differences between those groups as well,” Lindgren notes, “to see if cued gesturing has distinct effects for different populations.”

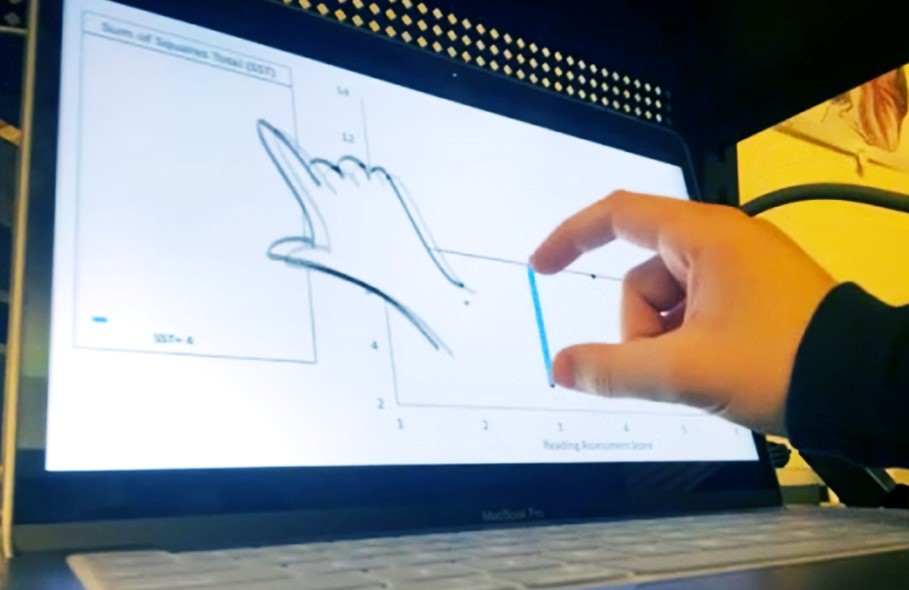

Instructors, Lindgren says, can sometimes be too quick to symbolize statistical concepts “in ways that can overly abstract the ideas. When you’re trying to understand something like linear regression, focusing on the distance of the various points to the regression line becomes really important in understanding conceptually what a regression line represents. So, while the gestures themselves are not particularly complex, they’re quite centering in terms of getting students to grasp the real-world spatial meaning of these concepts.”

Pandemic's Impact on Project

The project was accelerated by the pandemic, which generated an ever-increasing dependency on communicating and learning online. That dependency emphasizes the need to understand how to enhance communication online, through gestures, Perry says.

“One of the many unfortunate things that came out of the pandemic is that it really narrowed and limited our horizons when it came to the role that technologies can play in educational contexts,” Lindgren notes. “We were in a period where we were getting very excited about augmented reality, virtual reality, haptic computing, and mobile devices. But then the pandemic hit, and it became very much about whatever you could do within Zoom or other video conferencing spaces. That has reduced the space of expressing one’s learning to what I can fit in this little Zoom box that’s meant mostly for my head.”

So, the research team decided to work with the constraints of digital video while finding ways to make the experience of learning from video more physical and body-based.

“We did some really nice pilot work during the pandemic where we were able to create a prototype video that used animation to signal where and when students should hold their hands to represent specific statistical ideas,” Lindgren says. “We worked with students over Zoom and had them watch the video while we observed them make the gestures they were being cued to perform.”

Thinking With Your Hands

Research shows that gesturing works, Perry says. “When you get students to gesture, their understanding of the concept changes,” she explains. “It turns out that their understanding reflects the nuances or the specifics that are produced in their gestures.”

The study is critical, Perry adds, because “so much information is lost when we communicate on Zoom or online. You look at a lot of instructional videos in math generally or in statistics in particular and there’s almost no gesturing.”

“And so we said, ‘Well, it doesn’t have to be that way.’ We can call on students to notice gestures, we can produce gestures in the instructional videos, and we can cue students to produce those gestures themselves.”

Perry gives the example of using gestures when talking about variance or distance from the line of best fit and about indicating outliers quite far from the line. As she does, she quells a common misconception about gesturing.

“A lot of the questions I’ve had are about some people not gesturing at all,” she says. “That’s not true. Even blind people gesture, and they gesture in meaningful ways.”

“And it’s not about the size of the gesture. Some cultures are very expressive, and some are very restrained. But they express the same thing, whether the gesture is large or small.”

Using Video in More Creative Ways

Lindgren believes the project is particularly important in light of the increasing use of technologies in education, including the use of video conferencing.

“This project and hopefully others that will follow will show that, even in that context, there’s still a role for the body, for physicality, to play in communicating and learning,” he says. “There’s nothing particularly novel about digital video; it’s ubiquitous in our learning spaces. But how the viewing of the video is framed and how students engage with the video seems to really matter. Currently, digital video in educational contexts is primarily used to show each other’s heads as we’re talking, but we believe it can be used in more creative and powerful ways, to do things such as cueing students’ movement.”

“One cool potential outcome of this project is that we can do some pretty transformative kinds of interactions with relatively simple technologies that keep it embodied and physical.”

The project is exploring, in part, how gestures can enhance learning.

“We’re trying to figure out exactly what it is about producing gestures, and how that happens in the video learning space, that can support more students in learning these relatively difficult constructs,” Perry says. “Where the concepts are hard for them to understand, the gestures might give them a leg up towards a better understanding.”

Impact Across Many Disciplines

This project could impact students, educators, and others beyond the field of statistics.

“Everybody’s struggling a bit in the field of educational design, particularly when it comes to using technologies,” Lindgren says. “I think any guidance that we’re able to give in terms of how to use these technologies effectively to achieve enhanced learning will be well received.”

Perry sees the impact spreading across many disciplines.

“We hope eventually to come up with design principles to support others’ work that will support learning across different concepts in STEM disciplines and beyond,” Perry says. “There’s a lot to learn here, and I’m excited to be part of this project.”