Building Connections: Educating Navajo Youth About Their Community and History

by Tom Hanlon / May 21, 2024

Oliver Tapaha has always had a special place in his heart for his home.

Tapaha, an Illinois Distinguished Postdoctoral Research Associate Fellow, grew up in Round Rock, Arizona, a community of 600-some Native Americans in the heart of Navajo Nation. A citizen of the Diné/Navajo tribe, Tapaha went to Arizona State University to earn B.A. degrees in sociology and elementary education and later earned his Ed.M. and Ph.D. in education from Oregon State University. (“Diné” means “The People” in the Navajo language.)

Sandwiched around those degrees were returns home, where he taught for 12 years in a K-12 tribal school and two public school districts on the Navajo reservation. He also held two administrative posts at Diné College in Tsaile, Arizona, about 23 miles southeast of Round Rock, and from 2021-2023, Tapaha served as principal of the Round Rock K-8 School that he attended as a youth.

Coming to Illinois to conduct his postdoc work in the College's Education Policy, Organization & Leadership department might have taken Tapaha far from his home. But it hasn’t removed his homeland from his heart.

“I wanted to stay connected to my home community and the school I attended during my childhood years,” says Tapaha, a soft-spoken, genial, and thoughtful man. “It’s important to me that I’m still giving back in some way. I was taught to get an education and give back to my community. Home is always home, so I’m going to stay connected to the community that raised and taught me, even from a distance.”

Project Goal

He found that way through CHEII (Collaborative for Harmony, Empowerment, and Innovation, Inc.), a nonprofit from Round Rock that he was invited to be a board member of. CHEII was founded by Faith Roessel, the daughter of the late Robert and Ruth Roessel, who created the Rough Rock Demonstration School in 1966. That school, about 30 miles southwest of Round Rock, was formed on the same principles that CHEII now operates under.

“Our goal is to support and educate Navajo youth and families about how to improve life on the reservation, whether through cross cultural education, through intergenerational transmission of knowledge, or through community service projects,” Tapaha says.

Through CHEII, Tapaha has been involved in the Round Rock Community History Project with the school he attended and later was principal of: Round Rock K-8 School. The school has about 75 students.

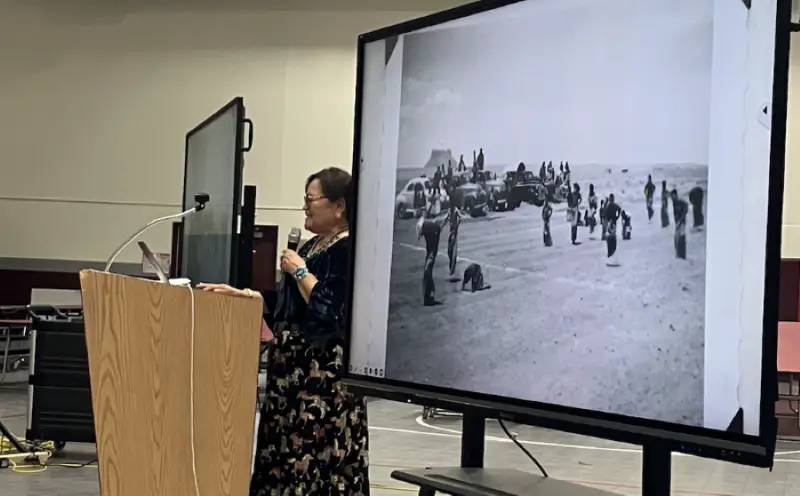

Faith Roessel leads a presentation for the Round Rock Community History Project.

Learning From Elders

Not coincidentally, in the Diné language, Cheii means grandfather. Part of the project involves students interviewing their elders and documenting their life stories, Tapaha says. During the spring semester, an elder talked to the students about historical events that happened in Round Rock.

“We also interviewed some community members about anything they wanted to share about Round Rock,” Tapaha says. “We recorded the interviews and will archive them with the CHEII organization. Students’ work and interview transcripts will be housed in the school library as curriculum resources.”

The project, funded by Dr. Jenny Davis, associate professor of Anthropology and American Indian Studies and the Collaborative Indigenous Research Pedagogy Program at Illinois, is centered around lessons on various topics, including traditional Navajo foods and nutrition, arts, the outdoors, life stories, and family histories that come from living on the reservation.

“We want to help students become researchers, historians, and archivists of their community,” Tapaha says. “We want them to understand the different ways they can connect to the community, the family, and the land. History is not just in the books. They learn history by connecting and collaborating with their elders in the present. That’s the most beautiful thing to me.”

A Collaborative Effort

Tapaha has worked with directors and staff at the university's Library Archives and Spurlock Museum of World Cultures, as well as the Newberry Library in Chicago to organize and provide virtual tours and presentations for the Round Rock students.

“The university library archives staff conducted a virtual presentation on the Flagstaff All-Indian Pow Wow, which was held from 1929 to 1979 in Flagstaff, Arizona,” Tapaha says. “They also shared archival documents from a 1964 interview about a young Havasupai boy who was taken by a Navajo family.”

Spurlock Museum provided two virtual tours about Indigenous peoples in North, Central, and South America and held a discussion about NAGPRA (the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act). The Newberry Library delivered a virtual presentation on Indian relocation in the 1950s and ‘60s. The Indian Relocation Act of 1956 was promoted as an attempt to provide vocational training for Native Americans, though many saw it as a thinly-veiled attempt by the government to remove Native Americans from their reservations and assimilate them into the general population in urban areas, thus weakening community and tribal ties.

Teaching About Social Justice

While Tapaha notes that he had a couple of uncles who moved from Round Rock to Chicago during this movement, and returned to the reservation equipped with trade skills that helped them do well, he also shared with the students that it is important to listen to the stories from the virtual presentations and the elder interviews to learn about the racism and injustice that their ancestors faced.

“As educators, it’s important that we touch on that in our classrooms, that we teach about social justice,” he says.

For example, Tapaha says, many of the students’ family members have experienced racism in the towns that border the reservation. “And the Chicagoland Indians lived in really impoverished areas,” he notes. “The BIA [Bureau of Indian Affairs] sent out some pamphlets and used them as propaganda to get Native Americans interested in relocating to cities, but when they moved there the conditions were horrible. They lived in unsafe housing units, children didn’t receive a quality education, and adults didn’t get sustainable jobs, just temporary jobs to get by. These are counter stories that are important for students to hear.”

The Flagstaff All-Indian Pow Wow was moved 10 miles north of the city because the townspeople no longer wanted so many Native Americans congregating in one area. The decision effectively canceled the Pow Wow.

“Those are topics we need to bring to the classroom and discuss,” Tapaha says.

Expanding Their Reach

Tapaha and others (Sam Slater, President of the Diné Studies Conference, and Nathan Tanner, doctoral candidate in EPOL) involved in the Round Rock Community History Project are documenting their work and hope to develop materials for other communities to use in similar projects. This pilot project, he says, will run through next spring.

“By next summer, we hope to have enough materials to share with local tribal communities,” he says. “We’d like to get this project published, even if it’s just a guidebook to share with community members and schools. We’re trying to expand this project in many different ways.”

One of those ways is through a presentation this summer that Tapaha will make with Bethany Anderson of the University Library Archives, Elizabeth Sutton of the Spurlock Museum, and Krystiana Krupa of the University of Illinois' NAGPRA Office, at a conference in Mexico City. “This is important work that Indigenous communities or communities in general could benefit from,” he says.

Positive Feedback

The feedback from teachers and students has been very positive, Tapaha says. “One teacher said it helped students to appreciate their community,” he recalls. “Another teacher, after seeing the Newberry presentation on Indian relocation, said ‘I felt like I took the long trip to Chicago myself. What we didn’t know before, we’re learning now, and we’ll learn more, and I love that.’”

The students love the material because, Tapaha says, “this is new information for them, and it is information they can relate to because it’s about Navajo.”

He shared a few quotes from some of the students:

- “I enjoyed the virtual tours because they got to show us the library in Chicago... I learned that there are a lot of different and unique Native Americans all over the United States." Girl, Seventh Grade

- "I talked with my grandma (about the Flagstaff All-Indian Pow Wow) and she said, ‘Oh wow, I didn't know!’ It had an impact on me, and it was cool and awesome." Boy, Seventh Grade

- “This project is important because I got to learn new things about Round Rock.” Girl, Fourth Grade

- “It’s important to talk about our family.” Boy, Third Grade

Taking Pride in Community and Culture

This knowledge and pride that the project has engendered in students—in their community, their ancestors, and themselves—thrills Tapaha and tells him that the project has been a success.

“Taking pride in who you are and where you came from is so important,” he says. “That’s why this community-engaged work is so critical.”

And that’s why, wherever he is, Tapaha will always stay connected to his home community.