Alumna starts College of Adaptive Arts to make a difference in the lives of diverse learners

by Sal Nudo / Jul 17, 2014

Many aspiring teachers receive their Education degrees from Illinois with the intention of one day leading a classroom and educating students to the best of their abilities.

For 12 years, DeAnna Pursai, M.Ed. ’96 EPOL, of San Jose, Calif., did just that. Her career after Illinois began in Seattle, where she taught behaviorally disordered children. A move to the Bay Area with her husband, Sridhar, led her to teaching a day class for special-needs children and later third-graders. Thanks in part to her Illinois degree she has held titles such as reading intervention coach, title I resource specialist, and district office instructional coach.

“I love the interdisciplinary nature of my degree,” said Pursai, who took courses in sociology, psychology, economics, philosophy, and policy. “It was a solid foundation, and I’m using every element in my role of starting up a brand-new non-profit business in an area that’s not been done much. You’ve got to grab deep down into your tool bag, and I felt like Illinois set me up with a pretty deep tool bag all these years later.”

"I love the interdisciplinary nature of my degree."

Inspired by Angel, her 40-year-old sister with Down syndrome, Pursai co-founded the College of Adaptive Arts (CAA) with Pamela Lindsay, a professional actress from Normal, Ill., who is pursuing her doctorate in educational leadership. Their mission was to provide educational opportunities in a collegiate environment that led to expanded career choices—a first-of-its-kind arts college for adults of any age with any type of disability.

The life paths of those with disabilities is limited by age 22, after official schooling ends, and Pursai knew that many young adults with disabilities had potential that was going untapped. Like any good entrepreneur, Pursai and Lindsay saw a need in society and took action.

“Over and over, systematically,” said Pursai, “the opportunities of special-needs adults are dramatically reduced when they ‘age out’ at age 22, and not just opportunities but services. Our feeling is that they have the right to continue to have an educational environment as much as any adult who wants to continue his or her higher education.”

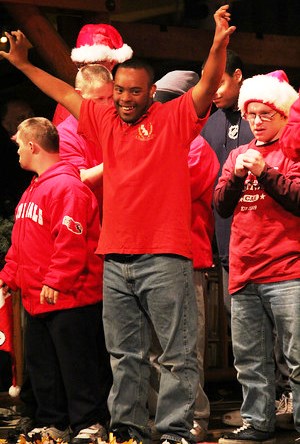

Pursai said the school has students who are blind, deaf, and schizophrenic, as well as students with autism, Down syndrome, and physical disabilities; approximately 15 percent have medical issues that are significant. The students can choose from a wealth of interactive classes such as dance, poetry/journaling/songwriting, concert choir, speaking with confidence, latizmo hip-hop dance, guitar basics, and clay animation. At the privately funded, currently non-accredited school, everything is dictated by what the families say they need.

Pursai said the school has students who are blind, deaf, and schizophrenic, as well as students with autism, Down syndrome, and physical disabilities; approximately 15 percent have medical issues that are significant. The students can choose from a wealth of interactive classes such as dance, poetry/journaling/songwriting, concert choir, speaking with confidence, latizmo hip-hop dance, guitar basics, and clay animation. At the privately funded, currently non-accredited school, everything is dictated by what the families say they need.

“The reason for starting the College of Adaptive Arts is because the families told us they needed it desperately,” said Lindsay, who is dean of instructional programs and curriculum. “We always look to them to say, ‘What is it you need? Are we on track? Are we moving in the direction that you need us to go to serve your adults in this area where they need this gap filled?’”

Judging by its growth, the listening process is working. What began as a school for 12 students in July 2009 has evolved into 20 part-time teachers teaching hundreds of students who have attended the school, now close to 70 adults every academic quarter. The cost is reasonable at $225 per quarter, and scholarships are available.

Pursai said having an intensely focused vision, positive relationships, and healthy work environments are essential elements of a successful entrepreneurial enterprise. Passion for what you’re doing plays a big part as well, which Pursai said she absorbed from her Illinois professors.

Pursai said having an intensely focused vision, positive relationships, and healthy work environments are essential elements of a successful entrepreneurial enterprise. Passion for what you’re doing plays a big part as well, which Pursai said she absorbed from her Illinois professors.

“I appreciate the high caliber of instruction I received at Illinois. The professors were all just super-passionate about their particular areas, and I saw how much they wanted to convey that to the students,” she said.

Pursai recalled with fondness Professor Susan Fowler’s “academically challenging and rigorous” class, where she was the only master’s degree student in a classroom full of doctoral students.

“I thrived on her expectations,” said Pursai. “I just had the highest esteem for that lady.”

She said the highly approachable Professor Nicholas Burbules was one of three professors on the committee for her master’s thesis. Pursai appreciated his energy, articulateness, and open mind.

“Nick assisted me by engaging me to think differently, to ensure that my logic and reasoning were sound, and always helped me gain a fresh perspective each time I met with him. I was in awe of his intellect and expansive research base,” she said.

During her time as a schoolteacher, Pursai said she became an expert on gauging the things she could control and the things she couldn’t.

“Whatever is in your sphere control,” she said, “make sure you’re providing quality service and maintaining a healthy culture and positive relationships. Then pretty much anything is possible.”

Pursai’s sphere has evolved a great deal since becoming an entrepreneur. As CAA’s executive director, she handles the accounting, marketing, communications, grant writing, and development of the organization. Pursai realizes that great ideas and policies don’t always translate to smooth implementation, and that plans don’t always unroll the way they were envisioned. Nonetheless, she strives to see things through and keep everything in perspective.

“I think of my sister and her situation, and I think of so many families and their situation where they’re grappling with how to keep their children alive and how they’re trying to just fight to get them involved. It’s very humbling, and it makes my problems seem a whole lot less important,” she said.

“I think of my sister and her situation, and I think of so many families and their situation where they’re grappling with how to keep their children alive and how they’re trying to just fight to get them involved. It’s very humbling, and it makes my problems seem a whole lot less important,” she said.

CAA’s operational budget has quadrupled from $50,000 since the school’s inception to $200,000, and Pursai and Lindsay are attempting to provide living wages for themselves and their staff, a difficult endeavor since the school doesn’t fall into a category that would allow it to receive state funding. CAA’s six-member board of directors help create fundraisers and events throughout the year—a golf tournament and film festival are two of the big ones—but the financial model of the school remains a work in progress.

"It's very humbling, and it makes my problems seem a whole lot less important."

Still, the women are adamant that they don’t want CAA to be an adult day program, a vocational training program, or a therapeutic program, all programs that would help it receive state funding. They are building their own standards of accreditation for “an equitable diploma track for adults who can learn and want to learn,” according to Lindsay.

“We simply want to be an institution of higher education for adults with differing abilities who otherwise typically don’t have access to a college experience,” Pursai said.

“We simply want to be an institution of higher education for adults with differing abilities who otherwise typically don’t have access to a college experience,” Pursai said.

CAA has provided enriched lives for people who may need the assistance most. In return, Pursai said special-needs adults who are educated in the arts offer the gifts of joy, love, and connection.

“Us typical people can’t even hold a candle to it,” she said. “I like to think of it as training them to be contributors to the happiness economy versus contributors to the financial economy. It’s kind of a lofty vision, I know.”

Said by the graduate of a College where many ambitious goals have become spectacular realities.