Benefits of College's Education Justice Project extend beyond prison bars

by Sal Nudo / May 9, 2014

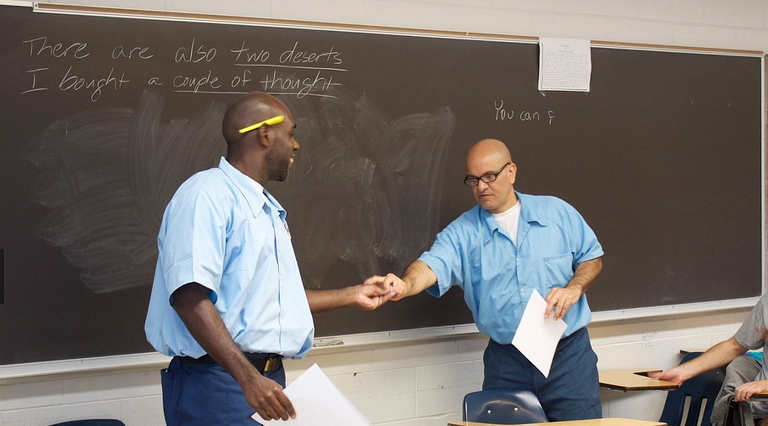

Orlando Mayorga is a Teaching Partner within the award-winning Language Partners program of the College’s Education Justice Project (EJP). Through training and coursework from University of Illinois faculty members and graduate students, Mayorga provides language instruction to men from the general population of the Danville Correctional Center, a medium-security prison.

Orlando Mayorga is a Teaching Partner within the award-winning Language Partners program of the College’s Education Justice Project (EJP). Through training and coursework from University of Illinois faculty members and graduate students, Mayorga provides language instruction to men from the general population of the Danville Correctional Center, a medium-security prison.

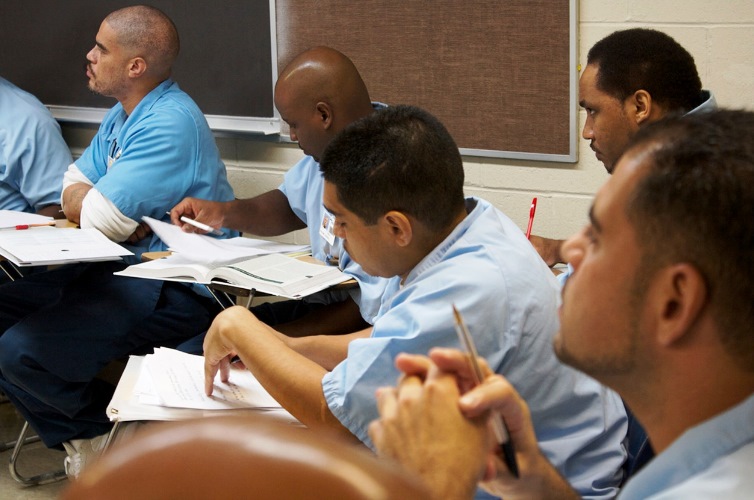

Mayorga, who hopes to become a counselor someday, is incarcerated at the facility. He is also a student and an English as a second language (ESL) instructor who is working to improve his life—and the lives of the men he resides with. The upper-division linguistic classes he’s taken through the University help him connect with and teach the many men in the facility who are fluent only in Spanish.

“It's very difficult to be a Spanish-only speaker at the prison,” said Rebecca Ginsburg, co-founder and director of EJP and an associate professor of Education Policy, Organization and Leadership. “You can't understand the orders the officers are giving you, you can't explain your symptoms to doctors and nurses. It's hard to socialize.”

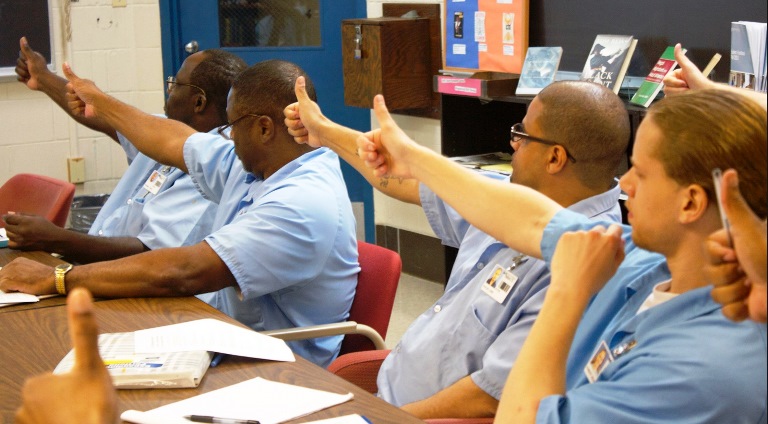

Becoming a Teaching Partner who educates the incarcerated men can help facilitate a better life after prison, according to Ginsburg. She noted two former Teaching Partners who are now working as full-time teachers in Mexico and one who does volunteer work as an ESL teacher in Cameroon.

“This is something that absolutely would not have been available to them had they not done this work with EJP,” she said.

This fall, EJP members and volunteers hope to begin the Chicago Anti-Violence Education (CAVE) program, using curriculum called SELF (Safety, Emotions, Loss, Future). The program operates under the theory that people who commit violence have experienced trauma in their lives and can address it to become healthier if they choose. In preparation for the launch, students in the prison are currently training to serve as facilitators and tutors to groups of young men in the facility’s general population.

This fall, EJP members and volunteers hope to begin the Chicago Anti-Violence Education (CAVE) program, using curriculum called SELF (Safety, Emotions, Loss, Future). The program operates under the theory that people who commit violence have experienced trauma in their lives and can address it to become healthier if they choose. In preparation for the launch, students in the prison are currently training to serve as facilitators and tutors to groups of young men in the facility’s general population.

Ginsburg said the goal of CAVE is to return the men to their communities as peacemakers.

“Through CAVE, they will have a better understanding of the costs of violence in society, emotionally and socially,” she said.

Ginsburg said the teachers in the facility—such as Mayorga—are appreciated for their skills and respected for the schooling they provide. She said the men who teach at the correctional center return to society better educated and more confident than when they entered prison. These improvements lead to possibly finding more meaningful employment and avoiding criminal activities.

Perhaps most significantly, Ginsburg said the reformed men often encourage their family members to pursue an education, breaking the intergenerational cycle of incarceration.

Perhaps most significantly, Ginsburg said the reformed men often encourage their family members to pursue an education, breaking the intergenerational cycle of incarceration.

“Society benefits in so many ways from this,” Ginsburg said. “Normally men in prison feel as if the outside world doesn’t care about them. When incarcerated people feel that they and their contributions are valued, they're better able to go back into the world and contribute to society in numerous consequential ways.”

Opinion piece in New York Times: Discover the advice Orlando Mayorga offered an eighth-grade boy.